- Visibility 275 Views

- Downloads 29 Downloads

- Permissions

- DOI 10.18231/j.jdpo.2019.065

-

CrossMark

- Citation

Diagnostic utility of thyroid fine needle aspiration cytology using The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology: A one year prospective study

- Author Details:

-

Chhavi Gupta *

-

Subhash Bhardwaj

-

Sindhu Sharma

Abstract

Introduction: Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology (FNAC) is the first line diagnostic procedure for evaluating thyroid lesions. The present study was carried out to assess the diagnostic utility of thyroid FNAC using The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology.

Materials and Methods: It was a one year prospective study conducted in the Department of Pathology, Government Medical College, Jammu and included all patients presenting with thyroid swelling referred to this department. The thyroid fine needle aspirates from these patients were classified into six categories according to The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. The Risk of Malignancy was calculated for each Bethesda category by follow-up histopathology. Sensitivity, Specificity, Positive Predictive Value (PPV) and Negative Predictive Value (NPV) were also calculated using histopathology diagnosis as gold standard.

Results: Thyroid fine needle aspirates from a total of 300 patients were classified according to Bethesda system as Nondiagnostic (ND)- 17cases(5.67%), Benign- 264cases(88%), Atypia of Undetermined Significance (AUS)- 1case(0.33%), Follicular Neoplasm(FN)-6cases(2%), Suspicious for malignancy(SFM)- 0case( 0%) and Malignant- 12cases(4%). The Risk of Malignancy was Nondiagnostic-50%, Benign-0%, AUS-0%, FN-50%, Suspicious for malignancy-not possible, Malignant-100%. Sensitivity, Specificity, PPV and NPV were 100%, 100%, 100%, 100% (FN excluded); 80%, 100%, 100%, 96% (FN included as benign); and 100%, 95.83%, 83.33%, 100% (FN included as malignant).

Conclusion: The present study concludes Bethesda system to be an effective reporting system for thyroid cytology, FNAC to be a sensitive and specific test for evaluation of thyroid lesions and FNAC using Bethesda guidelines is useful in risk assessment of thyroid nodules thereby guiding appropriate management.

Introduction

Thyroid diseases are among the commonest endocrine disorders worldwide. About 42 million people in India suffer from thyroid diseases according to a projection from various studies on thyroid disease.[1] Thyroid cancer is the most common endocrine malignancy, constituting 0.1%–0.2% of all cancers in India with an age-adjusted incidence of 1 per 100,000 in males and 1.8 per 100,000 in females.[2] Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is the first line diagnostic procedure for evaluating thyroid lesions. It is a simple, rapid, cost-effective test that provides valuable information about the nature of a thyroid nodule, can effectively distinguish between neoplastic and non‑ne oplastic lesions of the thyroid and permits the triage of patients for follow-up or surgery thus reducing unnecessary surgery for patients with benign disease.[3],[4]

FNAC, however, has certain inherent limitations e.g. it cannot differentiate follicular and Hurthle cell carcinomas from their benign counterparts as it cannot establish the presence of capsular and/or vascular invasion. Also, thyroid FNA suffers from variability in its diagnostic terminology.[5] Several classification schemes have been suggested including Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology, American Thyroid Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologist, but none of them have been universally accepted.[6],[7]

Reporting of thyroid FNA specimens should follow a standard format that is clinically relevant in order to direct appropriate management.[8] The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology (TBSRTC), a six-category scheme proposed by National Cancer Institute at a conference in Bethesda, United States in 2007 represents a major step towards a uniform reporting system for thyroid FNA that facilitates interpretation of thyroid FNA results in terms that are succinct, unambiguous and clinically useful, by pathologists and referring clinicians. Each of the categories has an implied malignancy risk (ranging from 0% to 3% for the benign category to virtually 100% for the malignant category) that links it to a rational clinical management guideline.[9],[10]

The present study was carried out to assess the diagnostic utility of thyroid FNAC using The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology.

Materials and Methods

It was a one year prospective study from Nov. 2017 to Oct. 2018 conducted in the Department of Pathology, Government Medical College, Jammu. It included all patients presenting with thyroid swelling referred to this department from various clinical departments of this hospital and from other health care centers. Non-cooperative and morbid patients were excluded from the study.

FNAC was performed using 22-24G needle and 20cc syringe. Smears were prepared; air dried smears were stained with May-Grunwald-Giemsa (MGG) stain and alcohol fixed smears were stained with Papanicolaou (PAP) stain. Stained smears were examined under light microscopy. The adequacy was assessed as per Bethesda criteria and the thyroid fine needle aspirates were classified into the six categories according to The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology i.e. Nondiagnostic /Unsatisfactory (ND/UNS), Benign, Atypia of Undetermined Significance/Follicular Lesion of Undetermined Significance (AUS/FLUS), Follicular Neoplasm/Suspicious for Follicular Neoplasm (FN/SFN), Suspicious for Malignancy (SFM) and Malignant categories. The definitions and cytomorphological criteria as described in The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology atlas were followed.[10]

The cytology diagnosis was compared with corresponding histopathology diagnosis wherever surgery was performed and Risk of Malignancy was calculated for each Bethesda category. Sensitivity, Specificity, Positive Predictive Value (PPV) and Negative Predictive Value (NPV) were calculated using histopathology diagnosis as gold standard. For this, Nondiagnostic and Atypia of Undetermined Significance cases were excluded as nondefinitive diagnosis and categories Suspicious for Malignancy and Malignant were together considered as malignant. All the parameters were calculated either excluding Follicular Neoplasm (FN) or including it with either benign or malignant diagnosis to highlight the effect on statistical values.

Results

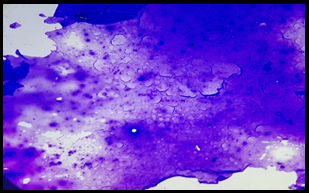

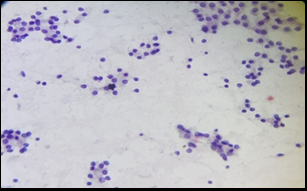

A total of 300 patients were included in the study. Thyroid fine needle aspirates from these patients were classified according to TBSRTC as Nondiagnostic (ND)- 17 cases (5.67%), Benign- 264 cases (88%), Atypia of Undetermined Significance (AUS)- 1 case (0.33%), Follicular Neoplasm (FN)- 6 cases (2%), Suspicious for malignancy (SFM)- 0 case (0%) and Malignant- 12 cases (4%) ([Table 1]) ([Figure 1],[Figure 2]).

Benign category was the largest category followed by Nondiagnostic category. Benign follicular nodule was the predominant subcategory followed by chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis. Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma was the most common malignancy reported in our study ([Table 1]).

All patients were followed for surgery, out of which histopathology diagnosis was available for 32 patients. The Risk of Malignancy for each Bethesda category calculated by comparing cytologic diagnosis with corresponding histopathologic diagnosis is shown in [Table 2] . The risk of malignancy for Suspicious for Malignancy category could not be calculated as no case was reported in this category.

Sensitivity, Specificity, Positive Predictive Value (PPV) and Negative Predictive Value (NPV) were 100%, 100%, 100%, 100% (FN excluded); 80%, 100%, 100%, 96% (FN included as benign); 100%, 95.83%, 83.33%, 100% (FN included as malignant) ([Table 3]).

| Bethesda Category | Sub-categories | Number of cases | Percentage (%) |

| I. Non diagnostic | 17 | 5.67 | |

| Cyst fluid only | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Virtually acellular specimen | 14 | 4.67 | |

| Others (obscuring blood, clotting artifact, etc.) | 3 | 1.00 | |

| II. Benign | 264 | 88.00 | |

| consistent with a benign follicular nodule (colloid nodule, adenomatoid nodule) | 183 | 61.00 | |

| consistent with chronic lymphocytic (Hashimoto) thyroiditis | 75 | 25.00 | |

| consistent with granulomatous (subacute) thyroiditis | 2 | 0.67 | |

| Other | 4 | 1.33 | |

| III. Atypia of Undetermined Significance | 1 | 0.33 | |

| IV. Follicular Neoplasm | 6 | 2.00 | |

| Follicular Neoplasm | 5 | 1.67 | |

| Follicular Neoplasm, Hurthle Cell (Oncocytic) type | 1 | 0.33 | |

| V. Suspicious for Malignancy | 0 | 0.00 | |

| VI. Malignant | 12 | 4.00 | |

| Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma | 5 | 1.67 | |

| Poorly differentiated carcinoma | 1 | 0.33 | |

| Medullary thyroid carcinoma | 2 | 0.67 | |

| Undifferentiated (Anaplastic) carcinoma | 3 | 1.00 | |

| Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | 1 | 0.33 | |

| Total | 300 | 100.00 |

| Bethesda category | Cytology Diagnosis | No. of cases with available histopathology diagnosis | Histopathology Diagnosis | No. of cases which turned out to be malignant | Risk of Malignancy (%) |

| I. Non diagnostic | 17 | 2 | Colloid Goitre=1 Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma, thyroid=1 | 1 | 50% |

| II. Benign | 264 | 23 | (Colloid Goitre, Nodular Goitre)=21 Follicular Adenoma=2 | 0 | 0% |

| III. Atypia of Undetermined Significance | 1 | 1 | Follicular Adenoma=1 | 0 | 0% |

| IV. Follicular Neoplasm | 6 | 2 | Colloid Goitre=1 Insular Carcinoma=1 | 1 | 50% |

| V. Suspicious for Malignancy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| VI. Malignant | 12 | 4 | Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma=3 Anaplastic Carcinoma=1 | 4 | 100% |

| Total | 300 | 32 | 32 | 6 | - |

| Cytology Diagnosis | Histopathology Diagnosis | Total | |

| Benign | Malignant | ||

| I. Non diagnostic | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| II. Benign | 23 | 0 | 23 |

| III. Atypia of Undetermined Significance | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| IV. Follicular Neoplasm | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| V. Suspicious for Malignancy | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| VI. Malignant | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Total | 26 | 6 | 32 |

Discussion

TBSRTC has been widely adopted in the United States and in many places worldwide and has been endorsed by the American Thyroid Association.[10],[11] The distribution of cases into various TBSRTC categories in our study were compared with other studies ([Table 4] ).

| Bethesda category | Present study | Mondal et al.3 | Mehra et al.4 | Bhat et al.12 | Laishram et al.13 | Jo et al.14 |

| I Non diagnostic | 5.67 | 1.2 | 7.2 | 6.6 | 5.2 | 18.6 |

| II Benign | 88 | 87.5 | 80 | 82 | 89.9 | 59 |

| III AUS | 0.33 | 1 | 4.9 | 2 | 0 | 3.4 |

| IV Follicular Neoplasm | 2 | 4.2 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 9.7 |

| V Suspicious for malignancy | 0 | 1.4 | 3.6 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 2.3 |

| VI Malignant | 4 | 4.7 | 2.2 | 5.1 | 2.2 | 7.0 |

The frequency of Non Diagnostic interpretations varies notably from laboratory to laboratory (range, 3-34%).[10] The findings of our study (5.67%) are consistent with this range and are comparable with studies by Mehra et al.,[4] Bhat et al,[12] and Laishram et al.,[13] ([Table 4]). Because most thyroid nodules are benign, a benign result is the most common FNA interpretation (approximately 60-70% of all cases).[10] The cases in benign category in our study (88%) are higher than this range and also differ from study by Jo et al.,[14] but are comparable with other studies.[3],[4],[12],[13] Being the only tertiary care center of our province, it caters to a large number of patients on both direct and referral basis, so a large population representative of general population is encountered that could be a reason for higher number of cases in benign category.

AUS cases reported in our study are comparable with studies by Mondal et al.,[3] and Laishram et al.,[13] and don't exceed upper limit of 10% as per Bethesda system.[10] Follicular Neoplasm cases reported in our study are also similar to other studies.[4],[12],[13] Suspicious for Malignancy (SFM) diagnoses account for approximately 3% (range 1.0-6.3%) of all thyroid FNAs. As with any indeterminate diagnosis, this category should be used judiciously so that patients are managed as appropriately as possible.[10] No case was reported under this category in our study. A malignant thyroid FNA diagnosis accounts for approximately 5% (range, 2-16%) of all thyroid FNAs.[10] Malignant cases (Category VI) in our study are within this range and are comparable with other studies.[3],[12]

The risk of malignancy for Benign and Malignant categories have corroborated with implied risks mentioned in the Bethesda System,[10] and also with other studies available in literature,[14],[15],[16] as shown in [Table 5]. TBSRTC recommends clinical and sonographic follow-up for Benign category and surgical management for malignant category.[10]

| TBSRTC category | Risk of Malignancy (%) as per TBSRTC guidelines10 | Mondal et al.3 | Jo et al.14 | Arul et al.15 | Yassa et al.16 | Present Study |

| I Non diagnostic | 5-10 | 0 | 8.9 | 0 | 10 | 50 |

| II Benign | 0-3 | 4.5 | 11 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0 |

| III Atypia of Undetermined Significance | ~10-30 | 20 | 17 | 24.4 | 24 | 0 |

| IV Follicular Neoplam | 25-40 | 30.6 | 25.4 | 28.9 | 28 | 50 |

| V Suspicious for Malignancy | 50-75 | 75 | 70 | 70.8 | 60 | - |

| VI Malignant | 97-99 | 97.8 | 98.1 | 100 | 97 | 100 |

The implied risk of malignancy as per updated TBSRT C guidelines for lesions in Nondiagnostic category is 5-10%,[10] but reported malignancy rates in various studies in literature demonstrate significant variability between 2% and 70.6%.[17] TBSRTC recommends repeat aspiration with ultrasound guidance for this category.[10] In our study too, malignancy risk for this category is higher (50%) than the range. This could be explained by smaller denominator patients (2cases) with available histopathology diagnosis in this category as a result of which malignancy risk has been overestimated for this category. TBSRTC recommends repeat aspiration for this category which was not performed in one case and other clinical history (lymphadenopathy) or Ultrasound findings may have warranted excision biopsy in this patient after which it was diagnosed as malignant ([Table 2]).

The risk of malignancy for AUS category is much lower (0%) than the TBSRTC guidelines. This could be explained by lesser cases (only 1 case) reported in this category and this case only underwent surgery and was reported as benign on histopathology. TBSRTC recommends conservative management with repeat FNA or molecular testing in most cases of initial AUS interpretation.[10] The risk of malignancy for Follicular Neoplasm category in our study is higher than the TBSRTC guidelines as well as other published studies. Surgical management is recommended for this category supplemented by molecular testing.[10]

The correlation of cytology and histopathology diagnosis is an important quality assurance method as it allows cytopathologists to calculate their false postive and false negative results.[18] Sensitivity, Specificity, Positive Predictive Value (PPV) and Negative Predictive Value (NPV) calculated by cytologic-histopathologic correlation using histopathology diagnosis as gold standard were compared with other studies ([Table 6]).

| Studies | Criteria | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

| Mehra et al.4 | FN excluded | 76.92 | 88.46 | 76.92 | 88.46 |

| FN included as benign | 73.33 | 89.66 | 78.57 | 86.67 | |

| FN included as malignant | 78.57 | 81.25 | 64.71 | 89.66 | |

| Kulkarni et al.19 | FN excluded | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| FN included as benign | 66.7 | 100 | 100 | 92.9 | |

| FN included as malignant | 75.0 | 75.0 | 50.0 | 90.0 | |

| Present study | FN excluded | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| FN included as benign | 80 | 100 | 100 | 96 | |

| FN included as malignant | 100 | 95.83 | 83.33 | 100 |

If FN is included with malignant group, the sensitivity increases but specificity decreases with a decrement in positive predictive value. These findings of our study are consistent with studies by Mehra et al.,[4] and Kulkarni et al.,[19] ([Table 6]).

The present study shows that FNAC can be relied upon as an alternative to histopathology since it displays a quite high sensitivity and specificity (80-100%). However, it must be kept in mind that some categories have been rearranged for the purpose of analysis (e.g. higher sensitivity was achieved when FN was excluded and when included with malignant group while higher specificity was achieved when FN was included with benign category).

Conclusion

The findings of our study were consistent with other published studies available in literature. The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology has led to clear interpretation of the thyroid FNAC report against the usage of personalized descriptive terminologies for thyroid FNA reporting conventionally being followed in our institution therefore improving communication between pathologists and clinicians. The present study also concludes FNAC to be a sensitive and specific test for preoperative evaluation of thyroid lesions and FNAC using Bethesda guidelines is useful in risk assessment of thyroid nodules thereby guiding appropriate management.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Source of Funding

None.

References

- Unnikrishnan AG, Menon UV. Thyroid disorders in India: An epidemiological perspective. Indian J Endocr Metab. 2011;15:78-81. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal S, Jain D. Thyroid cytology in India: contemporary review and meta-analysis. J Pathol Transl Med. 2017;51:533-547. [Google Scholar]

- Mondal SK, Sinha S, Basak B, Roy DN, Sinha SK. The Bethesda system for reporting thyroid fine needle aspirates: A cytologic study with histologic follow-up. J Cytol. 2013;30:94-99. [Google Scholar]

- Mehra P, Verma AK. Thyroid cytopathology reporting by the Bethesda system: A two-year prospective study in an academic institution. Patholog Res Int. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Theoharis C, Schofield KM, Hammers L, Udelsman R, Chhieng DC. The Bethesda thyroid fine-needle aspiration classification system: year 1 at an academic institution. Thyroid. 2009;19(11):1215-1223. [Google Scholar]

- Baloch ZW, Livolsi VA, Asa SL, Rosai J, Merino MJ, Randolph G. Diagnostic terminology and morphologic criteria for cytologic diagnosis of thyroid lesions: a synopsis of the national cancer institute thyroid fine needle aspiration state of the science conference. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36(6):425-437. [Google Scholar]

- Layfield LJ, Cibas ES, Gharib H, Mandel SJ. Thyroid Aspiration Cytology: current status. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:99-110. [Google Scholar]

- . Orell SR, Sterrett GF. Orell & Sterrett's Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology. 5th ed. New Delhi: RELX India Private Limited. . 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cibas ES, Ali SZ. The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:658-665. [Google Scholar]

- . Ali SZ, Cibas ES, Eds. The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Definitions, Criteria and Explanatory Notes.2nd ed. Switzerland: Springer. . 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, Doherty GM, Mandel SJ, Nikiforov YE. American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26(1):1-133. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat S, Bhat N, Bashir H, Farooq S, Reshi R, Nazeir MJ. The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology: a two year institutional audit. Int J Cur Res Rev. 2016;8(6):5-11. [Google Scholar]

- Laishram RS, Zothanmawii T, Joute Z, Yasung P, Debnath K. The Bethesda system of reporting thyroid fine needle aspirates: A 2-year cytologic study in a tertiary care institute. J Med Soc. 2017;31(1):3-7. [Google Scholar]

- Jo VY, Stelow EB, Dustin SM, Hanley KZ. Malignancy risk for fine-needle aspiration of thyroid lesions according to the Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;134:450-456. [Google Scholar]

- Arul P, Akshatha C, Masilamani S. A study of malignancy rates in different diagnostic categories of the Bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopathology: An institutional experience. Biomed J. 2015;38:517-522. [Google Scholar]

- Yassa L, Cibas ES, Benson CB, Frates MC, Doubilet PM, Gawande AA. Long-term assessment of a multidisciplinary approach to thyroid nodule diagnostic evaluation. Cancer Cytopathol. 2007;111(6):508-516. [Google Scholar]

- Gunes P, Canberk S, Onenerk M, Erkan M, Gursan N, Kilinc E. A different perspective on evaluating the malignancy rate of non-diagnostic category of the Bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopathology: A single institute experience and review of the literature. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):162745-162745. [Google Scholar]

- Bagga PK, Mahajan NC. Fine needle aspiration cytology of thyroid swellings: How useful and accurate is it?. Indian J Cancer. 2010;47(4):437-442. [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni CV, Mittal M, Nema M, Verma R. Diagnostic role of the Bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopathology in an academic institute of Central India: one year experience. Indian J Basic Appl Med Res. 2016;5(2):157-166. [Google Scholar]

How to Cite This Article

Vancouver

Gupta C, Bhardwaj S, Sharma S. Diagnostic utility of thyroid fine needle aspiration cytology using The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology: A one year prospective study [Internet]. IP J Diagn Pathol Oncol. 2019 [cited 2025 Oct 28];4(4):320-326. Available from: https://doi.org/10.18231/j.jdpo.2019.065

APA

Gupta, C., Bhardwaj, S., Sharma, S. (2019). Diagnostic utility of thyroid fine needle aspiration cytology using The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology: A one year prospective study. IP J Diagn Pathol Oncol, 4(4), 320-326. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.jdpo.2019.065

MLA

Gupta, Chhavi, Bhardwaj, Subhash, Sharma, Sindhu. "Diagnostic utility of thyroid fine needle aspiration cytology using The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology: A one year prospective study." IP J Diagn Pathol Oncol, vol. 4, no. 4, 2019, pp. 320-326. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.jdpo.2019.065

Chicago

Gupta, C., Bhardwaj, S., Sharma, S.. "Diagnostic utility of thyroid fine needle aspiration cytology using The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology: A one year prospective study." IP J Diagn Pathol Oncol 4, no. 4 (2019): 320-326. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.jdpo.2019.065