Author Details :

Volume : 4, Issue : 1, Year : 2019

Article Page : 58-62

https://doi.org/10.18231/2581-3706.2019.0011

Abstract

Introduction: Granulomatous dermatoses are group of disorders which are caused by varied etiological agents and includes heterogenous lesions but often share a common histological feature of granuloma formation. Leprosy and cutaneous tuberculosis occupies the major proportion of this category. Leprosy is the most common chronic infectious granulomatous dermatoses caused by mycobacterium leprae. Cutaneous tuberculosis has varied mode of presentation.

Materials and Methods: The present study is a one year retrospective study carried out in the Department of Pathology. All the skin biopsies of leprosy cases received in histopathology section from September 2016 to August 2017 were reviewed from the archives of the department.

Results: Of 168 skin biopsies, 104 cases were included and remaining 64 cases were excluded. Among 104 cases, 96 cases were leprosy and 8 cases were tuberculosis. It included 73 males and 31 females. Most commonly affected age group was 21-40 years. Majority of the patients were found to have hypopigmented patch. Many of cases were borderline tuberculoid (26 cases) followed by lepromatous leprosy (18 cases). Among the 8 cases of tuberculosis, 4 were lupus vulgaris, 2 were cases of granulomatous chelitis and one cases each of papulonecrotic tuberculid and tuberculosis verrucosa cutis.

Conclusion: Diagnosis of leprosy cases should be an integrated approach and includes dermatological, histopathological and microbiological examination. Leprosy is the most common infectious granulomatous dermatitis encountered which was presented clinically with hypopigmented patch. It was found to more common in third and fourth decade of life. This is followed by cutaneous tuberculosis.

Keywords: Granulomatous dermatoses, Punch biopsy, Leprosy, Cutaneous tuberculosis, Hypopigmented patch.

Granulomatous dermatoses are group of disorders which are caused by varied etiological agents and includes heterogenous lesions but often share a common histological feature of granuloma formation.[1] Granuloma can be described as a focal chronic inflammatory response of a tissue characterized by aggregation of epithelioid cells and multinucleated giant cells, may or may not be rimmed by lymphocytes and with or without evidence of central necrosis.[2] Some of these histological lesions are caused by several causes and conversely, a single etiological agent may produce various histological patterns.[3] Leprosy and tuberculosis occupies the major proportion of this category.[1]Accurate diagnosis is of utmost importance as the treatment differs for different skin lesions.[4]

Leprosy is the most common chronic infectious granulomatous dermatoses caused by mycobacterium leprae.[5]It is also called as Hansen’s disease which was discovered by Sir Gerhard Armauer Hansen from Norway in the year 1873. The disease manifests with wide variety of clinical presentations, thus posing challenge to the treating doctors even after century of its discovery.[6] It poses a major public health problem worldwide. The disease is endemic predominantly in tropical and subtropical region including India, Southeast Asia, Africa and Brazil.[7]

Leprosy patients presents with wide clinico pathological manifestations, which mainly depends on the host-pathogen interaction altering the immune-pathologic response.[7] Diagnosis of leprosy cases should be an integrated approach and includes dermatological, histopathological and microbiological examination.[8] In 1966, Ridley and Jopling have classified leprosy into five categories based on the immunological status of the patients; such as Tuberculoid (TT), Borderline tuberculoid (BT), Midborderline (BB), Boderline lepromatous (BL) and Lepromatous (LL), which has been accepted worldwide.[9]The Indeterminate form (IL) includes cases that did not fit into any of the groups mentioned above.[10]

From therapeutic point of view, the Leprosy unit at World health organization (WHO) recommends ‘operational classification’ which is highly beneficial in the resources poor settings to conduct histological examination for acid fast bacilli. It includes 2 forms- paucibacillary type having upto five skin lesions with/without only one nerve trunk involved and multibacillary type with more than five skin lesions with/without more than one nerve trunk involved. An appropriate classification makes it helpful to initiate correct treatment at the earliest and reduce the spread of disease, chances of recurrences and morbidity of leprosy.[10]

Cutaneous tuberculosis (TB) is mainly an infection of skin and subcutaneous tissue caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It mainly affects through three routes such as, a) direct inoculation into skin (tuberculosis verrucosa cutis), b) hematogenous spread from internal organ (lupus vulgaris, military TB, tuberculous gumma), c) spread from underlying lymph node (scrofuloderma).[7] These varied presentation of cutaneous TB is mainly attributed to the route of infection, immune status of the patient and the previous exposure with the organism. Various diagnostic modalities for TB are histopathological examination of skin biopsy, demonstration of the AFB, microbiological cultures and ancillary techniques like PCR.[1]

Thus the present study was undertaken to analyze the clinical and demographic profile of the patients, to study the various histomorphological features and to correlate the clinico pathological profile of the infectious granulomatous dermatoses.

This retrospective study was carried out in the Department of Pathology, BLDE University’s Shri B.M. Patil Medical College, Hospital and Research Centre, Vijayapura, Karnataka.

All the skin biopsies received in histopathology section from October 2015 to September 2017 were reviewed from the archives of the department. Clinical history and demographic data were recorded. Slides stained with routine hemotoxylin and eosin stain and special stains such as Ziehl–Neelsen (ZN) stain, Fite-Ferraco stain were examined under light microscopy. Further they were classified into various histological categories according to Ridley Jopling classification.

Inclusion criteria: All the punch biopsies which were histopathologically diagnosed as infectious granulomatous dermatoses received in department were included in the study

Exclusion criteria: Inadequate skin biopsies and inconclusive biopsies were excluded from the study.

Results

Out of total 168 skin biopsies received, 104 cases were included in the present study and remaining 64 cases were excluded from the study. Among 104 cases, 96 cases were leprosy and 8 cases were tuberculosis. The present study included 73 males and 31 females with M:F ratio of 2.3:1. The most commonly affected age group in the present study was 21-40 years among both males and females constituting 52.06% and 45.13% respectively (Table 1).

The clinical presentation of the leprosy cases was varied in the present study (Table 2). Majority of the patients were found to have hypopigmented patch (52 cases, 54.17%), followed by erythematous lesions (22 cases, 22.92%), eczema (7 cases, 7.29%), xerotic patch (6 cases, 6.25%), hyperpigmented patch (4 cases, 4.17%). No lesions were observed in 5 cases.

The clinical diagnosis and the histopathological diagnosis were compared among all the cases of leprosy (Table 3). Majority of the cases were categorized as borderline tuberculoid (26 cases, 27.1%) on the basis of histological diagnosis followed by lepromatous leprosy (18 cases, 18.67%).

Bacillary index (BI) for the leprosy cases was also analyzed (Table 4). There were cases belonging to grade 1+ (5 cases), 2+ (6 cases), 3+ (6 cases), 4+ (7 cases), 5+ (17 cases) and 6+ (10 cases).

Among the 8 cases of tuberculosis (Table 5), 4 were histopathologically diagnosed as lupus vulgaris, 2 were cases of granulomatous chelitis and one cases each of papulonecrotic tuberculid and tuberculosis verrucosa cutis (TBVC).

Discussion

Granulomatous dermatitis is a chronic inflammatory response to antigenic stimulus. It includes a broad category, which was earlier classified based on the etiology, pathophysiology, morphology and immunology. At present, various authors tried to classify it based on the etiology and morphology of granuloma.[2],[11]

Infectious granulomatous dermatitis is most frequently encountered by pathologists. Leprosy and tuberculosis constitutes the most predominant cases among this category. It also includes other diseases like fungal infections which presents with granuloma on microscopy. Post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis closely resembles LL on clinical examination causing diagnostic dilemma.[2]

The mode of transmission of leprosy is unknown, but it is possibly thought to spread by inhalation and implantation of the organisms from soil which are contaminated by the nasal secretions of a multibacillary leprosy patient.[7]The most common sites involved are peripheral nerves and skin. However, eyes, muscles, bone, testes and mucosa of respiratory tract are also affected apart from the above sites.[5]Leprosy can be diagnosed by various methods which includes clinical examination of the skin lesions (can be either hypopigmented or erythematous patches) and peripheral nerves, demonstration of the acid fast bacilli (AFB) in the slit skin examination, histopathological examination of the skin biopsy and demonstration of AFB by modified Fite-Ferraco stain and Fine needle aspiration cytology of skin and nerves.[9]

In the present study many patients were belonging to third and fourth decade constituiting 52%, which were similar to study done by Sumit grover et al[1]and Agarwal et al.[3] Many of the cases presented clinically with hypopigmented patched (54.17%%), followed by erythematous lesions (22.92%%). However, hyper pigmented lesions were found in very few. Whereas, Veludurty et al[4] in their study has recorded hyperpigmented patch/plaque as the most common clinical presentation followed by hypopigmented patch/plaque.

The clinical spectrum of leprosy showed BT leprosy as the commonest condition followed by LL. This was similar to study done by Singh A et al.[9] In the present study, histopathologically confirmed BT cases constituted 26 cases (27.1%) followed by LL of 18 cases (18.67%), which was in concordance with study of Bal et al [2]and Kumbar et al.[11]

Histologically, TT leprosy was characterized by well formed granulomas comprising of epithelioid cells with rim of lymphocytes placed throughout the dermis, predominantly located around adnexal structures and neurovascular bundles encroaching basal epidermis. Whereas, granulomas with few lymphocytes and many giant cells not encroaching basal layer of epidermis were characteristic feature of BT leprosy. Cases typically composed of granulomas rich in foamy histiocytes and few epithelioid cells were categorized as BL leprosy. Cases with diffuse sheets of foamy histiocytes in dermis, separated from epidermis by grenz zone were characteristically seen in LL cases.[2]

Cases with epithelioid granulomas of BT and TT leprosy has to be differentiated form non-infectious granulomas seen in sarcoidosis and non-caseating tuberculous granulomas. Fite faraco stain is not found to be helpful in such condition as BI of BT and TT is usually low. In such instances, location of granulomas around neurovascular bundles, erector pili muscle and adnexa in combination with molecular test like polymerized chain reaction (PCR) is helpful in identification of the organism. However, PCR is not employed in the routine practice for diagnosis of leprosy.[2],[11]

Among the cutaneous TB cases (8 cases) observed in the present study, lupus vulgaris was the most common condition. None of the cases had AFB positive in ZN stain. This was in concordance with observation of Kumbar et al.[11] According to Veena et al[12]and Singh R et al,[13] AFB was found in only 6.45% and 11.5% of cases respectively.

Table 1: Age wise distribution of all cases included in the present study

|

Age distribution (years) |

Males (number) |

Percentage (%) |

Females (number) |

Percentage (%) |

|

<10> |

2 |

2.74% |

1 |

3.26% |

|

11-20 |

5 |

6.85% |

4 |

12.9% |

|

21-30 |

20 |

27.4% |

8 |

25.81% |

|

31-40 |

18 |

24.66% |

6 |

19.32% |

|

41-50 |

9 |

12.32% |

3 |

9.64% |

|

51-60 |

14 |

19.19% |

5 |

16.13% |

|

61-70 |

3 |

4.1% |

3 |

9.68% |

|

>70 |

2 |

2.74% |

1 |

3.26% |

|

Total |

73 |

100 |

31 |

100 |

Table 2: Various clinical presentations observed in leprosy cases.

|

S. no |

Clinical feature |

Number of cases |

Percentage (%) |

|

1 |

Hypopigmented patch |

52 |

54.17% |

|

2 |

Erythematous lesions |

22 |

22.92% |

|

3 |

Eczema |

7 |

7.29% |

|

4 |

Xerotic patch |

6 |

6.25% |

|

5 |

Hyper pigmented lesion |

4 |

4.17% |

|

6 |

No lesion |

5 |

5.20% |

|

7 |

Total cases |

96 |

100 |

Table 3: Comparison between clinical diagnosis and histopathological diagnosis in cases of leprosy.

|

Clinical diagnosis |

Histopathological diagnosis |

||||||

|

TT |

BT |

BB |

BL |

LL |

HL |

IL |

|

|

TT |

5 (5.21%) |

2 (2.1%) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

BT |

3 (3.13%) |

26 (27.1%) |

0 |

1 (1.04%) |

0 |

0 |

2 (2.1%) |

|

BB |

0 |

1 (1.04%) |

1 (1.04%) |

3 (3.13%) |

1 (1.04%) |

0 |

0 |

|

BL |

0 |

3 (3.13%) |

1 (1.04%) |

6 (6.25%) |

2 (2.1%) |

0 |

1 (1.04%) |

|

LL |

0 |

3 (3.13%) |

4 (4.17%) |

3 (3.13%) |

18 (18.67%) |

0 |

1 (1.04%) |

|

HL |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

9 (9.37%) |

0 |

|

IL |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Table 4: Bacillary index (BI) of various leprosy cases.

|

Bacillary index (BI) |

Number of bacilli observed |

Number of cases |

|

1+ |

1 Bacilli in 100 fields |

5 |

|

2+ |

At least 1 bacilli in every 10 fields |

6 |

|

3+ |

At least 1 bacilli in every field |

6 |

|

4+ |

At least 10 bacilli in every field |

7 |

|

5+ |

At least 100 bacilli in every field |

17 |

|

6+ |

At least 1000 bacilli in every field |

10 |

Table 5: Cutaneous tuberculosis cases included in the present study.

|

S. no |

Cutaneous tuberculosis |

Number of cases |

Percentage (%) |

|

1 |

Lupus vulgaris |

4 |

50% |

|

2 |

Papulonecrotic tuberculid |

1 |

12.25% |

|

3 |

Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis |

1 |

12.25% |

|

4 |

Granulomatous chelitis |

2 |

25% |

|

5 |

Total |

8 |

100 |

|

Click here to view |

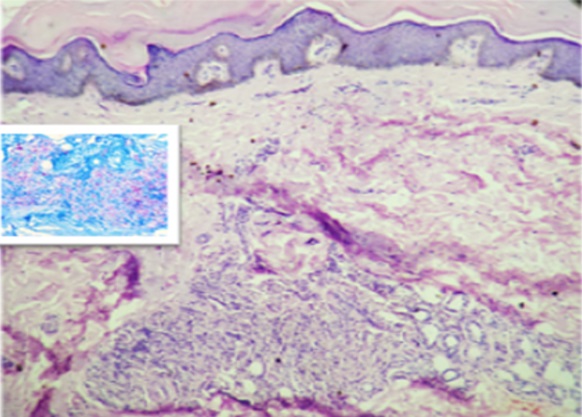

Fig. 1: lepromatous leprosy (H&E, 100x) Insite: Fite faracco staining showing acid fast positive lepra bacilli.

|

Click here to view |

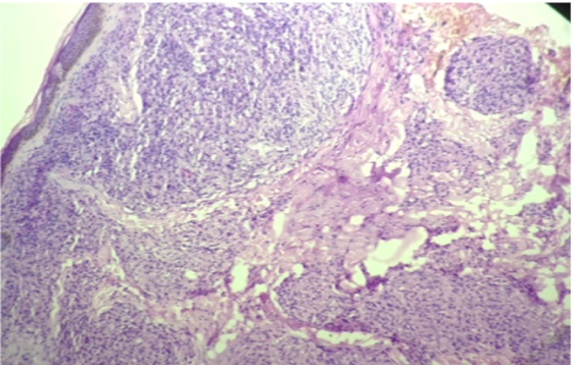

Fig. 2: Histioid leprosy (H&E, 100x)

Diagnosis of leprosy cases should be an integrated approach and includes dermatological, histopathological and microbiological examination. Leprosy is the most common infectious granulomatous dermatitis encountered which was presented clinically with hypopigmented patch. It was found

to more common in third and fourth decade of life. This is followed by cutaneous tuberculosis.

Conflict of Interest: None.

How to cite : Susmitha S, Mamatha K, Sathyashree Kv, Pyla R, Prashant K, Infectious granulomatous dermatoses: Clinico-histopathological correlation in punch biopsy specimens. IP J Diagn Pathol Oncol 2019;4(1):58-62

This is an Open Access (OA) journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Viewed: 2111

PDF Downloaded: 473