- Visibility 342 Views

- Downloads 61 Downloads

- Permissions

- DOI 10.18231/j.jdpo.2020.084

-

CrossMark

- Citation

Lymphangioma of the dorso-lateral tongue in an adult male: A rare case report

- Author Details:

-

Kafil Akhtar *

-

Fatima Meraj

-

Fauzia Talat

-

Sadaf Haiyat

Abstract

Lymphangioma is a relatively uncommon benign tumour occurring due to malformation of the lymphatic vessels. Lymphangioma in adults is a rare occurrence. Intraoral lymphangiomas occur most frequently on the dorsal tongue and rarely on the palate, buccal mucosa, gingiva and lips. Clinically, lymphangiomas of the oral cavity usually have a plaque formed of small thin-walled vesicles and similar in surface to frog eggs. We present a case of lymphangioma of the tongue in a 34-year-old male who presented with complaints of painless swelling in his tongue with difficulty in speaking for the last 25 days. CT scan revealed a lobulated sharp-contoured soft tissue communicating with the superficial planes with minimum vascularity in colour doppler studies. En masse excision of the firm, solid erythematous mass was performed which microscopically showed multiple dilated endothelial lined vessels filled with a proteinaceous fluid and lymphocytes. A diagnosis of lymphangioma of the tongue was given.

Introduction

Lymphangioma, described by Redenbacher in 1828, is a relatively uncommon benign tumour occurring due to malformation of the lymphatic vessels.[1], [2] These tumours comprise 4% of all the vascular tumours and 25% of all benign vascular tumours in children. No racial predominance or sexual predilection has been reported in them. [3] They are also called lymphatic hamartomas and are usually detected at birth (50%) or in early childhood, and the majority (90%) of congenital cases develop before two years of age.[4] Lymphangioma in adults is a rare occurrence.[4]

The head and neck region is frequently involved (50%–75%) in lymphangiomas; however, the oral cavity is rarely affected. Other sites include shoulder, armpit, abdomen, neck, pharynx, eyelids, and conjunctiva.[5] Intraoral lymphangiomas occur most frequently on the dorsal tongue and rarely on the palate, buccal mucosa, gingiva and lips. [6] Tongue lymphangiomas represent 6% of these tumours in the body.[7], [8] The most common site for intraoral lymphangioma leading to macroglossia is the anterior two-thirds of the dorsal surface of the tongue.[9]

Case Report

A 34-year-old male reported to the otolaryngology Clinics of Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College Hospital with chief complaint of a painless swelling on his tongue for 25 days. The patient also had difficulty in speaking and accidental biting of tongue while eating. Intraoral examination revealed a solitary inflamed fleshy swellingon the left dorsolateral part of the tongue, approximately 3x4 cm in size, with numerous tiny papillary projections. On palpation, the lesion was soft and tender with adherence to the superficial and deep layers. There was no bleeding on palpation, as well as no evidence of any lymph nodes. No other intraoral lesions were appreciated. The cranial nerve examination was within normal limits. The patients’ vital signs were stable.

Routine blood investigations showed all parameters within the normal range. Indirect laryngoscopy showed no extension to the vocal cords and larynx. CT scan revealed a lobulated sharp-contoured soft tissue communicating with the superficial planes. Minimum vascularity was present in colour doppler studies.

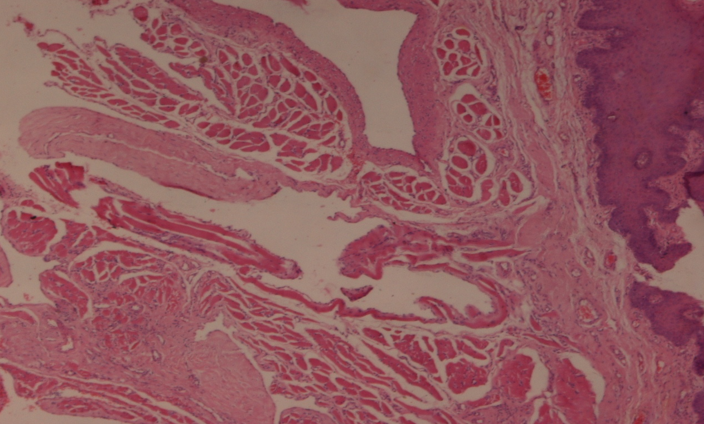

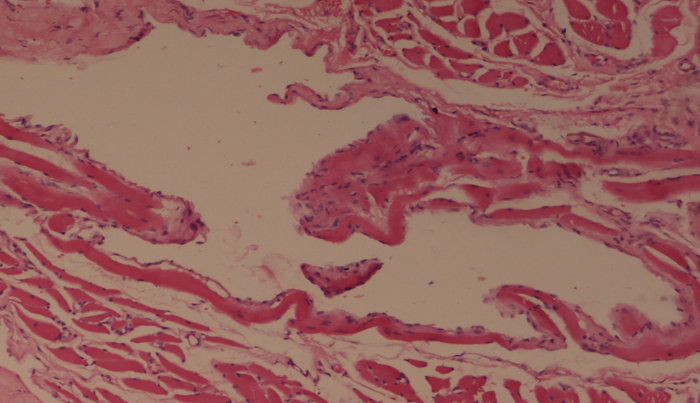

En masse excision was done using local anesthesia with a margin of 1 cm from the lesion. The excision mass was firm, solid erythematous and measured 3.5 x 4.2 cm. Histopathological examination of the lesion showed multiple dilated endothelial lined vessels just adjacent to squamous epithelium. These vessels contained proteinaceous fluid and lymphocytes ([Figure 1], [Figure 2]). A diagnosis of lymphangioma of the tongues was given. Our patient is doing well after 12 months of follow up period.

Discussion

The etiology of lymphangioma is not fully understood, and two major theories are proposed. The first theory explains that the lymphatic channels develop from 5 primitive sacs arising from the venous system and endothelial out-pouching from the jugular sac forms the lymphatic system in the head and neck region. The second theory proposes that the mesenchymal clefts in the venous plexus reticulum extend towards the center of the jugular sac and form the lymphatic system. Congenital obstruction or sequestration of these enlarged primitive lymphatics leads to lymphangioma.[9] On the other hand, the etiology of lymphangioma acquired in adulthood is different and includes trauma, inflammation, and lymphatic obstruction.[5]

Lymphangioma is typically diagnosed clinically. The extension and size of lesion affect the clinical appearance of lymphangioma. Superficial lesions are pink or yellowish in color and consist of elevated nodules. The deeper lesions are soft and diffuse masses with mild variation in color.[6] Clinically, lymphangiomas of the oral cavity present as pinkish small thin-walled vesicular lesions. The vesicles contain both clear fluid (lymph) and blood content suggesting the co-existence of lymphatic and vascular anomalies.[10]

De Serres LM in 1995 proposed a classification for lymphangiomas of head and neck based on anatomical extent, which can be used to the predict prognosis and outcome of surgical intervention This system branched lymphangiomas into unilateral infrahyoid lesions (stage I), unilateral suprahyoid lesions (stage II), unilateral suprahyoid and infrahyoid lesions (stage III), bilateral suprahyoid lesions (stage IV) and bilateral suprahyoid and infrahyoid lesions (stage V).[2]

Macroglossia, with an irregular surface displaying gray and pink projections, is a key feature of lymphangioma of the tongue. In children, lymphangioma is a common cause of macroglossia and is associated with difficulty in swallowing and mastication, speech disturbances, airway obstruction, mandibular prognathism, bleeding, and other deformities of maxillofacial complex.[9] Majority of cases of macroglossia in children due to intraoral lymphangioma are located on the anterior two-thirds of the dorsal tongue.[11]

Lymphangiomas are classified histopathologically into lymphangioma simplex (capillary lymphangioma), cavernous lymphangioma and cystic lymphangioma (cystic hygroma).[7]

Due to their characteristic histology and classic clinical appearance, lymphangiomas of the tongue are easy to diagnose. The histologic features are characteristic and the clinical appearance often classic. Generally, any “bump of the tongue” is included under the clinical differentials of lymphangiomas. Hematoxylin and eosin stained sections are best for differentiating them from other differentials. In the present case, the dorsolateralsite may suggest entities such as granular cell tumor, lingual thyroid, and mesenchymal tumors, but are not limited to these. Vascular lesions like hemangiomas, venous malformations and arteriovenous malformations are the main mesenchymal tumors to be considered.[3]

Among the hemangiomas, the infantile hemangiomas show the most resemblance to lymphangiomas. These are mostly congenital and occur frequently in the head and neck. However, they involute after some years whereas tongue lymphangiomas do not regress. The classic frog egg clinical appearance is absent in hemangiomas. Infantile hemangiomas may show marked endothelial proliferation which is missing in lymphangiomas. There is no close connection to the superficial epidermis as in lymphangiomas, and they are very reactive (95%) to GLUT-1.Lymphangioma can be distinguished from the vascular lesions by the increased expression of D2-40 in lymphatic endothelium.[5]

Venous malformation also tend to be present at birth and persist like lymphangiomas. Clinically, they may be red or blue, having nodules or blebs very similar to a lymphangioma. However, venous malformations are typically compressible and may demonstrate a thrill or bruit, whereas lymphangiomas will not. Histologically, venous malformations are composed of aberrant vessels often times dilated, filled with red blood cells. Endothelial cell proliferation is generally not a feature of vascular malformations.[3] Arteriovenous malformations are less common and can have excessive bleeding on biopsy. Tissue may show variable sized vessels, thrombosis and calcification. [11]

Pyogenic granuloma is a localized reactionfound mostly in the gingiva, but also frequent on the tongue. Clinically, pyogenic granulomas may be sessile or pedunculated red to pink mass. Histologically, they may resemble granulation tissue witha vague lobular architecture of the vessels. Pyogenic granulomas may be very inflamed, demonstrating both acute and chronic inflammation with or without ulceration.[3]

Early recognition and appropriate treatment is necessary to achieve optimal therapeutic results and avoid complications.[12], [13] Lymphangioma is managed on the basis of their type, size, anatomical structures involved and infiltration to the adjacent tissues.[13], [14] The main purpose of therapy is to relieve pain, edema, lymph, and blood leak, as well as super infections. Aesthetic improvement is also important for patients psychological well-being. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice, but it causes scar formation and is not feasible in all cases. Cryotherapy, radiation therapy, steroid administration, sclerotherapy, electro-cautery, embolization, ligation, laser surgery, and radiofrequency tissue ablation are the other modalities used in such cases. It is essential to include a surrounding border of normal tissue without damaging vital structures for minimal recurrence and successful outcome.[15], [16]

Source of Funding

No financial support was received for the work within this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Bhayya H, Pavani D, Tejasvi MLA, Geetha P. Oral Lymphangioma: A Rare Case Report. Contemp Clin Dent. 2015;6(4):84-7. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Serres LMd, Sie KCY, Richardson MA. Lymphatic Malformations of the Head and Neck: A Proposal for Staging. Arch Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg. 1995;121(5):577-82. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Eren S, Cebi AT, Isler SC, Kasapoglu MB, Aksakalli N, Kasapoglu C. Cavernous lymphangioma of the tongue in an adult: a case report. J Istanb Univ Fac Dent. 2017;51(2):49-53. [Google Scholar]

- Goswami M, Singh S, Singh A, Gokkulakrishnan S. Lymphangioma of the tongue. Nat J Maxillofac Surg. 2011;2(1):86-8. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Hoff SR, Rastatter JC, Richter GT. Head and Neck Vascular Lesions. Otolaryngol Clin North Am . 2015;48(1):29-45. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Nelson BL, Bischoff EL, Nathan A, Ma L. Lymphangioma of the Dorsal Tongue. Head Neck Pathol. 2020;14(2):512-5. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Vardhan BGH, Muthu MS, Rathan JJ, Venkatachalapathy, Saraswathy K, Sivakumar N. Oral lymphangioma: A case report. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent . 2005;23(4):185-9. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Kayhan KB, Keskin Y, Kesimli MC, Ulusan M, Unur M. Lymphangioma of the tongue: Report of four cases with dental aspects. Kulak Burun BogazIhtis Derg. 2014;24(3):172-6. [Google Scholar]

- Mayank M, Manolkar RM, Mhapsekar RV. Lymphangioma of tongue: A case report and review of literature. Int J Biomed Res. 2016;7:223-5. [Google Scholar]

- Mehmedovic Z, Mehmedovic M, Custovic MK, Sadikovic A, Mekic N. A rare case of giant mesenteric cystic lymphangioma of the small bowel in an adult: A case presentation and literature review. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2016;79(3):491-3. [Google Scholar]

- . WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumours. 4th Edition. International Agency for Research on Cancer Lyon. . 2017. [Google Scholar]

- FAM, SKL. Lymphatic Malformations. In: Skull Base Imaging. . 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Richter GT, Suen J, North PE, James CA, Waner M, Buckmiller LM. Arteriovenous Malformations of the Tongue: A Spectrum of Disease. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(2):328-35. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Shah AA, Mahmud K, Shah AV. Generalized lymphangioma of the tongue: A rare cause of macroglossia. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg . 2020;25(1):49-51. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Stănescu L, Georgescu EF, Simionescu C, Georgescu I. Lymphangioma of the oral cavity. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2006;47:373-7. [Google Scholar]

- TU, SS, GSJ, JA. Lymphangioma of the Tongue - A Case Report and Review of Literature. J Clin Diag Res . 2014;8(9):12-4. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

How to Cite This Article

Vancouver

Akhtar K, Meraj F, Talat F, Haiyat S. Lymphangioma of the dorso-lateral tongue in an adult male: A rare case report [Internet]. IP J Diagn Pathol Oncol. 2020 [cited 2025 Oct 26];5(4):434-437. Available from: https://doi.org/10.18231/j.jdpo.2020.084

APA

Akhtar, K., Meraj, F., Talat, F., Haiyat, S. (2020). Lymphangioma of the dorso-lateral tongue in an adult male: A rare case report. IP J Diagn Pathol Oncol, 5(4), 434-437. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.jdpo.2020.084

MLA

Akhtar, Kafil, Meraj, Fatima, Talat, Fauzia, Haiyat, Sadaf. "Lymphangioma of the dorso-lateral tongue in an adult male: A rare case report." IP J Diagn Pathol Oncol, vol. 5, no. 4, 2020, pp. 434-437. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.jdpo.2020.084

Chicago

Akhtar, K., Meraj, F., Talat, F., Haiyat, S.. "Lymphangioma of the dorso-lateral tongue in an adult male: A rare case report." IP J Diagn Pathol Oncol 5, no. 4 (2020): 434-437. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.jdpo.2020.084